‘Tell Me How You Eat’: A conversation on food, purpose, and recovery, with author Amber Husain

Our modern eating disorder recovery strategies focus heavily on refeeding and regaining, limiting our experiences to numbers and measurable outcomes—the same things that made some of us sick in the first place. But what if recovery was more than this?

What if, by understanding the history of humans’ relationships with food, we got a clearer picture of why issues might arise? And what if recovery wasn’t just about food, but about finding purpose?

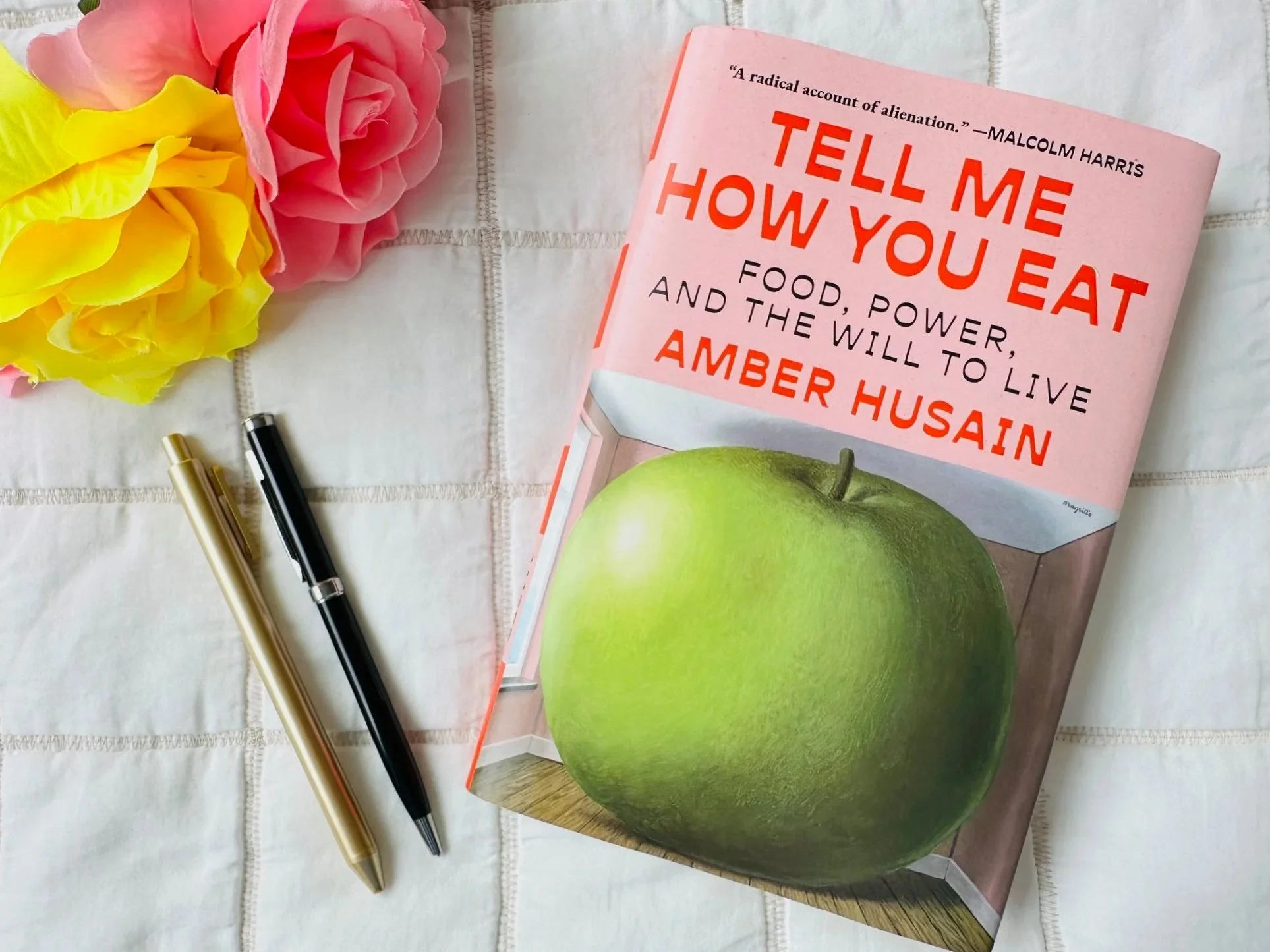

These are questions Amber Husain explores in her new book, Tell Me How You Eat: Food, Power, and the Will to Live. Well-researched, heartfelt, and honest, the book presents recovery as a way back into the world: to purpose, relationships, and the possibility of a life that’s worth living.

This month, I had the pleasure of interviewing Husain about some of these ideas, which you can find below. To learn more about the book and to buy a copy, click here!

For readers meeting you for the first time, can you share a bit about yourself and what led you to write Tell Me How You Eat?

Of course. Tell Me How You Eat is my first full-length non-fiction book, but it develops the kinds of interests that have driven me in the past as a writer of essays and criticism, and as an academic. Very broadly: the things that make life worth living—pleasure, love, creativity—and the social and political currents that come between us and those things.

I wrote the book at a moment when I was feeling a great sense of liberation—of coming back into contact with pleasure, excitement, and inspiration, after a period of anorexia, introspection, and general listlessness.

I was conscious that my route to feeling better was quite an unusual one, and given that standard treatments for eating disorders are acknowledged to be somewhat limited in their effectiveness, it felt important to ask myself what had gone so differently in my case. I knew it had something to do with restoring my will to live, my sense of hope for the world around me, and my sense of having a role (together with others) in trying to change it. But I wanted to understand better how food had figured in this. Why my despair had manifested in a struggle to eat, and how and why food and eating had been important to regaining it.

We tend to think about eating, and eating disorders, in terms of what they say about us, rather than what they say about what happens around us, and this can be more harmful, in my view, than it is helpful. The book is an attempt to make sense of this, and to encourage readers, too, to ask questions about how food and eating connect us with the wider world.

You write about having to “prove” your eating disorder to participate in a study. What did that experience reveal to you about how our world defines “sick enough”?

I think it’s always important to put these things in material context, and while there are slightly different dynamics at play in the US and the UK (where I’m based), there are also some continuities.

In the UK, we have state-funded healthcare, but a system that is increasingly underfunded to the point of crisis. Since the 1980s or thereabouts, the National Health Service (NHS) has been increasingly reorganized around (I would argue misguided and short-sighted) principles of ‘efficiency’. This has led to a bizarre attempt to make psychological and social illnesses fit certain ‘objectives’, measurable criteria, which are addressed only at ever deeper levels of severity. From the perspective of the NHS, you need to be ‘value for money’, meaning you need to be able to show measurable improvement in hospital, which is measured by weight. This is obviously disastrous.

On a practical level, it means people descend further into illness as they wait for treatment, and when the treatment finally comes, it fails to address anything meaningful about the problem. Things like suffering, the nature of suffering, and the collective nature of suffering aren’t measurable, and therefore aren’t of interest to the medical system.

We see something similar in the US, only the arbiters of illness and gatekeepers of medicine are, to a great extent, insurance companies.

You suggest the DSM can flatten lived experience into a label: “The DSM will try to tell you who you are, not the nature of your experience.”

Where do you see diagnosis helping in recovery, and where can it limit or miss the fuller story?

The best thing that can be said for diagnosis is that it puts an illness in social context, showing people that they’re not alone in their suffering, and pointing to a problem that demands societal attention. Unfortunately, in the case of eating disorders, diagnoses are rarely used this way. Because our treatments are generally focused on simply correcting individual patients’ behaviour, rather than understanding their illnesses at their root, the diagnosis simply works to mark individuals out for correction—to pathologise, to stigmatise, to shame.

In writing about Eleanor Marx: “The doctor saw a need for Eleanor both to be nourished and afforded a sense of purpose…a person isn’t inspired to start eating again by nothing more than other people’s advice."

What role do you think meaning or purpose plays in eating disorder recovery?

Whatever the specific cause of a person’s eating disorder, the refusal to eat amounts to a kind of withdrawal from life. You can try and scare someone back into eating by telling them how much damage they are doing to themselves, but if they’re half-checked-out of living, and no longer value things like health, longevity, energy, and so on, then you aren’t going to get very far.

To eat is to nourish life, and if you want someone to do that, you’re going to have to help them find motivation to live. So in that sense, wherever it comes from—whether it’s simple pleasures or loving friendships or political purpose—inspiration and motivation are going to be basic.

In writing about your veganism intersecting with restriction, you state, “Reams of medical research are concerned with the high proportion of vegetarians among people with eating disorders. Though they cannot agree on a cause, the papers generally conclude by warning that a meat-free diet can serve to mask and maintain the symptoms of illness.”

How can someone tell when a value is truly theirs versus when it might be quietly protecting their eating disorder?

If eating disorders are a kind of withdrawal from life, which I argue they are, I think you can tell when a dietary impulse has to do with investing in life and the world around you, or whether it’s more of a retreat into the self, and preoccupation with your own, individual body.

If you follow a vegan diet because you care about animals, or workers’ rights, or object to the cheapening of life by the capitalist food system, then it’s likely that, even if you’re struggling to eat in general, this will be helping you to eat, at least something. Whereas if you don’t really care about those kinds of things, then I can see how adopting a vegan diet could be just another form of restriction, a turning inward.

You challenge narrow definitions of health: “If the aim is a healthier life, perhaps we ought to ask if there is more to life and health than calorie intake, female fertility, a number on a scale, a person’s fitness to work…What if life were better measured by feeling alive, connected with the world, or faithful in the future possibility of justice?”

If we widened our definition of health beyond numbers and productivity, what might recovery start to look like?

That’s such a beautiful and important question. I think it could look so many different ways depending on what matters to the person recovering, but very broadly, I think it would be a curious and collaborative process, one that takes each patient’s suffering seriously as meaningful, but also which encourages and inspires them to look outside of themselves for new sources of meaning, hope, and inspiration.

I don’t think this is something that can necessarily be achieved quickly or efficiently or even ‘measurably’ in the scientific sense. I think we can learn from practices like psychoanalysis here, which are long-term, exploratory, and relational, dissecting what happens between the patient and the person they’re talking to. But individual therapies can only get us so far; we then have to go out and live, and that’s something we need to learn as a society to support each other to do.

To those reading this who are either in recovery or just beginning to question their relationship with food, what’s one idea from this book you hope they can carry with them?

That their suffering isn’t something to hide or quietly ‘correct’, and is certainly not a cause for shame, but rather should be a cause for asking questions: about what matters to them, and how, together with others, they can try and live in the direction of what matters to them.

Learn more about Tell Me How You Eat, and order a copy here.

Pause & Prompt

When you imagine a life worth living, what does it look like?

How to maintain recovery when everything around us feels unstable.